Cyprus receives more energy from the sun per square metre than anywhere else in Europe and yet there is no end in sight to our energy woes

By Karim Arnous

“Between May and September this year, we paid €1,633 for our electricity bill,” explains Christina, of Limassol.

Andreas, also from Limassol, said that his electricity bills seriously eat into monthly budgeting, and sacrifices were having to be made. “Over two months in the summer our bill was €1,055. We don’t use the ACs excessively – only when we need to. We have two young kids, it’s difficult to sit in the heat all day.”

Why, specifically, are bills so high? And what can be done to improve matters?

Cyprus still produces over 80 per cent of its electricity by burning heavy oil at its three thermal power stations. This creates an inextricable link between oil prices and power prices. The price of Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO) burned by the generators is up significantly within the last three years, and with the Organisation for Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) recently announcing coordinated efforts to drive oil prices even higher, it is unlikely the near future will bring any relief.

The price of procrastination

Compounding matters, the type of oil has such a high carbon intensity that Cyprus now routinely oversteps its quotas of emissions credits as prescribed in the European Trading Scheme (ETS). The idea of the scheme is to create a financial incentive for countries to reduce their carbon footprint. Over time, the EU lowers the cap, making allowances scarcer and thus encouraging further emission reductions. It’s a market-driven approach to tackling climate change, aiming to find the most cost-effective ways to cut emissions across the continent.

EAC filings show that €596.6 million was spent on credits between 2017 and 2022. Worryingly, this has been increasing rapidly in recent years, with €247.9m paid out in 2022 alone (19 per cent of their operational expenses that year). If distributed equally, this would be a surcharge of around €500 per household per year, but in reality this burden is disproportionately borne by those households without solar, as the surcharge is priced into the unit rate of power.

With the emissions quota decreasing annually, the penalty paid into the ETS is only going to rise unless significant progress is made in decarbonising the energy sector.

What about solar?

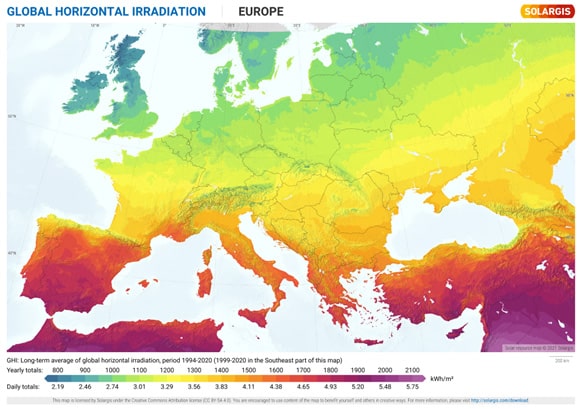

The island’s status as a laggard on the decarbonisation front comes despite best-in-Europe solar irradiance. A solar panel installed in Cyprus yields approximately double the energy as a panel installed in the UK. What’s more, owing to extraordinary declines in panel costs over the last decade, solar energy is now the cheapest energy source in history when installed within certain longitudes, with a levelised cost (total lifetime production divided by total costs, discounted to the present day) now below €0.03/kWh – approximately 10 times less than the unit rate currently paid by consumers.

Unfortunately, issues with the grid in Cyprus have made building new utility solar extremely difficult. Even where connections can be found, a lack of ‘flexibility’ in the system means solar investors must contend with the risk of being curtailed (switched off) by the central operator at times of high production. This risk is dramatically increasing as more solar is installed.

“Part of the challenge stems from Cyprus’ grid being isolated and small,” explains Dr Andreas Procopiou, a renewable energy expert, who has conducted leading research at posts in the UK and Australia before recently returning to Cyprus.

“In managing electricity grids, the frequency must be kept stable at all times to avoid a blackout. Due to solar’s intermittent nature, it can’t be relied upon without some sort of flexible asset that can fill the gaps. With no storage systems currently installed, the [transmission system operator] TSO manages this risk by keeping the oil generators running on low at all times. This means that even on a sunny day when solar is producing all the island’s electricity needs, oil turbines will still be running, producing 100s of MWs of stable energy. To balance the surplus when total generation exceeds demand, solar will be curtailed to ensure grid reliability.”

According to numbers collated by PV Magazine, an average of 21 per cent of renewable generation was curtailed each day over the first four months of the year. On some days, as much as 70 per cent was curtailed. This is where the TSO is sending a signal to reduce solar production output at times when the grid is overloaded, essentially throwing that energy away. So far, this is primarily affecting utility solar, but with rooftop installations on the rise (despite calls from the operator to suspend licences for this very reason) the problem may spread to residences. Until recently, only residential installations larger than 7.14kW had ‘ripple’ control, allowing them to be remotely turned down by the operator. Now, following recent changes to regulation, all PV systems must include this provision.

“It’s a shame,” says Procopiou, “but without any kind of storage, the grid operator has no choice.”

So what’s the way forward? There are a few options on the table.

Gas

Much has been made of the island burning natural gas, given this could be sourced from within Cyprus’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Gas is between 20-40 per cent cleaner to burn per unit of generated electricity than oil, and is often referred to as a ‘bridging’ solution in decarbonisation efforts. Gas generation, however, would still subject Cypriot consumers to the volatility of the international commodity market – a fact Northern Europeans know only too well after the recent war-induced market turbulence and ensuing energy crisis.

The island’s projects also seem to be suffering from a murky timeline. Type in ‘Power Generation EAC’ online and the first result is a page explaining that three turbines at Vasilikos will be switched over to gas ‘by 2016’.

While negotiations with US extraction giants have advanced, they recently hit a bump as Cypriot representatives disagreed with Chevron’s proposal to remove processing infrastructure from the sea surface near the extraction site (within Cyprus’ EEZ) and instead pipe the gas straight to Egypt, where it can be processed and liquified at existing facilities. On the generation side, with work at the first private gas plant in Cyprus recently halted due to environmental concerns, it remains uncertain when gas will make its debut in the Cypriot energy mix.

EuroAsia

The EuroAsia interconnector is a huge undersea high voltage electricity cable proposed to run between Israel, Cyprus and Greece. Reports suggest the first section will be completed by 2029 at a cost of €1.9 billion. Some €757m has been pledged by the EU through various mechanisms, with the rest to be financed between Cyprus and Greece (the countries involved in the first phase).

A ground-breaking project that will set multiple records, the EuroAsia interconnector would end Cyprus’ energy isolation and allow for smoother integration of solar into the system. However, there is inherent risk in infrastructure projects of this size.

No country in the world has ever installed a cable so long (1,200km) and so deep (3,000m+). While it would help to balance the grid, Cyprus would lose control of the carbon intensity of its power, relying on Greece and/or Israel having a clean power surplus to meet decarbonisation goals.

In July this year, after a long, detailed evaluation of the EuroAsia project, the European Investment Bank (EIB) denied an application for a construction loan. The viability study conducted by EIB was submitted to the government but has not been made public, despite plans for partial taxpayer funding. Separately, technical issues with the project were reported by ministers over the summer, but it was not made clear what these were.

Scepticism of EuroAsia is mounting. Last month, former finance minister Constantinos Petrides expressed serious concerns. On a post on platform ‘X’, he asked, amongst 20 damning questions, why the project still has no commercial investors, how no supplier agreements have been made despite the project being underway for over a decade and whether any technological advances have made the interconnector irrelevant.

Storage

Energy storage technologies are useful for storing renewable energy when there is excess and distributing it when needed. In the last few years, spurred by rapid uptake of electric vehicles and stationary storage projects, batteries have emerged as a leading technology in this space, with multiple ‘gigafactories’ contributing to increases in supply and significant cost reductions.

To date, Cyprus doesn’t have any energy storage systems in place. The government is considering running auctions for combined solar/storage projects, but nothing is yet confirmed. The major issue here is with the energy market.

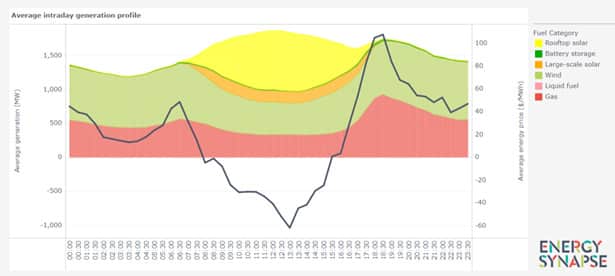

Energy storage naturally compliments renewable generators, which while cheap and clean, are intermittent and cannot be dispatched at will. In more functional energy markets, mechanisms allow the price of power to fluctuate many times per day (usually every half hour) to reflect the balance between supply and demand during that specific period.

At times where there is bountiful renewable supply, prices can fall, even going negative in sunny markets like Australia and California. When demand picks up and more expensive generators (usually gas) are required to meet needs, the price rises. This creates a recurring daily spread in energy prices which energy storage assets are able to trade. For storage operators, it’s like trading Forex, except where you know almost exactly what will happen every single day. The caveat is that it’s expensive to get into the game – you need to develop, build and maintain a big storage asset, but this hasn’t deterred billions of euros from flooding into this asset class globally.

For the system, the batteries’ trade is useful. They take cheap renewable power from a time where it is in surplus and redistribute it when people need it. Batteries can be used in other ways, too – they can respond so quickly to control inputs that they’re useful for regulating grid frequency – the type of fast-acting contingency you need in place in case a big cloud suddenly blocks the sun from a bunch of solar parks. Grid operators run markets to procure these services, with competitive auctions ensuring the grid’s needs are met at the lowest cost to the consumer.

Cyprus has no such energy market. While reform has been promised for over a decade now, persistent delays and issues mean this is unlikely until at least next year.

Without a privatised, fit-for-purpose energy market, there is no incentive for anyone, whether dependent on wholesale markets at the utility-scale or retail markets at the residential level, to install a battery.

Utility solar is paid for based on an ‘avoidance cost’ – that is, the price it would have cost EAC to produce that kWh of electricity at one of its thermal power stations had it not come from solar. This avoidance cost only changes monthly, allowing no intraday fluctuations to reflect supply/demand balances and resulting in an unfortunate dynamic where even renewably generated power is pegged in price to oil.

Similarly at the retail level, net-metering for home systems, while very attractive to installers, is not sustainable. Net-metering serves as an artificial battery system – when the panels produce more power than the house needs, exports to the grid roll back the metre, building credits which can be drawn upon many months down the line. It’s the perfect battery (at least on an accounting level) but it completely ignores the reality of the system – in a sunny country like Cyprus, the value of a unit of power at midday should be far lower than the value of that same unit later in the evening.

A reflection of this value differential, perhaps in the form of a feed-in-tariff (FiT) for residential solar could create the right environment for investment in storage, which would store excess power produced during the day for use later, also saving users on grid fees. Germany is a great example of this. The FiT applied to residential solar has meant one in every four photo-voltaic systems installed has a battery, with over 6,000MWhs of storage capacity already deployed across the nation’s homes.

The current mechanism in Cyprus strongly benefits those who can afford to install solar at the cost of those who can’t. While any changes to the net-metering regime or wholesale pricing system will be hard to swallow for recent installers, without deep market reform it’s hard to see how Cyprus will economically deploy the storage it needs.

Cyprus is blessed with excellent natural resources and has the potential to one day be a regional leader in the renewable energy space, saving consumers thousands annually and contributing meaningfully to the economy through the export of green fuels like hydrogen and ammonia for powering ships. Now more than ever, as the consequences of years of procrastination rear their heads and hard-pressed consumers buckle under the weight of utility bills, scrambling to try and install solar (which will only add to the system operator’s woes) it’s imperative that the government acts quickly, thoroughly and transparently.

Karim Arnous is a former business reporter at the Cyprus Mail and currently founder of London based energy optimisation startup, GridQ