In the mid-20th century, excavations at an ancient city caused a massive row between two archaeologists but answered the question of when the Greeks first settled in Cyprus

A classical archaeology expert has brought to life an ancient Cypriot kingdom and dug into the unpublished archival documents to reveal the clash between two men who excavated the city.

George Papasavvas’ recently published book also shows how scientific research into a Cypriot Late Bronze Age city near Salamis became embroiled in the mid-20th century politics of imperial powers, such as Britain and France. This, together with chance discoveries and personality clashes, makes for a fascinating story.

“Trench Warfare at Εnkomi: Personalities, Politics and Science in Cypriot Archaeology” tells the story of how local archaeologist Porphyrios Dikaios took on one of the world’s most renowned experts at the time – France’s Claude Schaeffer.

Papasavvas, associate professor of classical archaeology at the University of Cyprus, researched the unpublished archival documents kept in the Collège de France in Paris and in the Cyprus State Archive to reveal the story behind the excavation of ancient Enkomi.

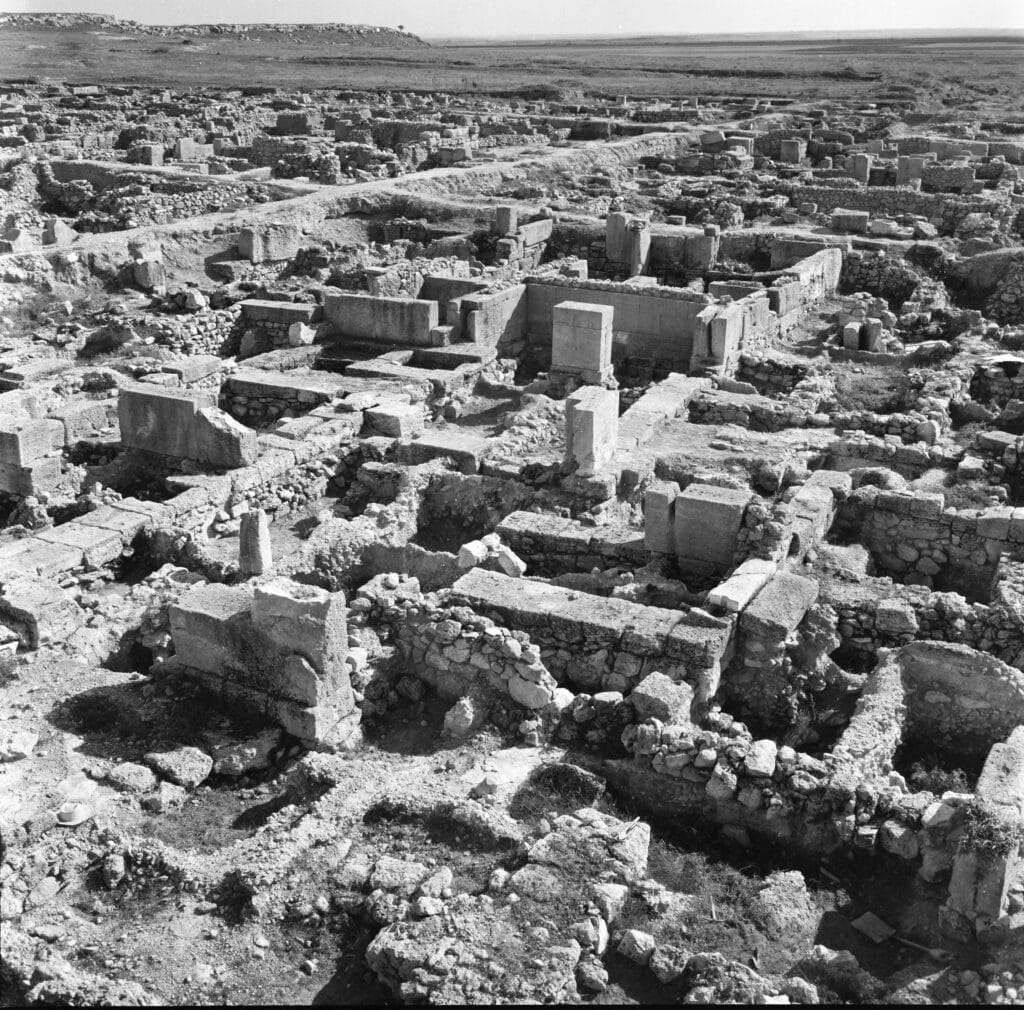

The city was abandoned around 1100 BC, when its inhabitants moved to the far more famous Salamis, which is situated two or three kilometres to the west of Enkomi. Called Alashiya in ancient in ancient Eastern and Egyptian sources, archaeologists have long adopted the name of the modern village, Enkomi, situated right next to the ancient site.

Papasavvas’ book outlines how the clash between Dikaios and Schaeffer reflects the wider political developments not only in Cyprus but also in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Near East in the period after World War II, as Britain and France were losing control of their colonial networks.

Archaeology, as so often, became entwined with politics and issues of national identity.

Control over the acquisition of antiquities from occupied or oppressed lands and their presentation in European museums became an integral part of western colonial activity and imperial power games, as well as a matter of national prestige.

Through the rivalry between Dikaios – who after independence became director of the antiquities department – and Schaeffer, together with the intervention of then British director of the Department of Antiquities, Peter Megaw, in favour of Dikaios, Papasavvas educates us on Cyprus’ crucial role in Mediterranean history of the Late Bronze Age – from about the mid-17th century BC to about the 1100s BC.

“At the time, the Cypriot king of this tiny island, called Alashiya in ancient Eastern and Egyptian sources, was communicating with the pharaoh of Egypt and was addressing him as ‘my brother’ – which was a major diplomatic privilege,” Papasavvas told the Cyprus Mail.

“Cyprus managed to enter the diplomatic, economic and political networks that were established by the great powers of the time – such as the Egyptians, Assyrians and Babylonians or the Hittites, the Mycenaeans too of course,” he says.

Papasavvas adds further context: “All that because of the island’s access to the prolific local deposits of copper, the metal that was of much importance for economic transactions in the ancient world.”

Ancient history can feel distant, remote, and sometimes even insignificant to our lives today – but Papasavvas explains that the major excavations which began at the site in the 1930s blew open some of the most controversial topics at the time, and in fact still today, such as: When did the Greeks – the Mycenaeans – arrive in Cyprus to settle? How did the island become hellenised?

The excavations at Enkomi provided much evidence for this discussion. But this proved to be a thorny issue.

“During British rule, to serve their politics and imperial strategies, the British were trying to convince the Cypriots of the day that they were not Greeks: they were Cypriots, plain and simple, not Greeks,” says Papasavvas.

“Let us remember that the excavations at Enkomi were conducted in the midst of political upheaval and the demands of the largest part of the population for independence and/or union with Greece.

“The British were falsely using some particular archaeological interpretations and prejudgements to argue that the character of Cypriot culture is very different and very idiosyncratic and does not have much to do with Greece,’’ Papasavvas explains.

“This came at the time when Greek Cypriots were fighting for union with Greece, so the timing of when the ancient Greeks first came to Cyprus suddenly became very important, not only for scientific but also for political reasons – the discipline of archaeology is very often exploited for political reasons.”

The associate professor also offered an added complexity: “There’s even a suggestion that when the British left the island in 1960, they began discussing the Mycenaeans as having arrived in Cyprus and collaborating with the locals – raising suspicions that they were more interested to portray themselves in that light of good will, mutual benefit and productive collaboration – which was of course not the case.”

The thinking there appears to be ‘well, the Greeks arrived as foreigners and enriched Cyprus – so have we’.

There was some controversy over when the Mycenaeans came to Cyprus, but Papasavvas explained that we must first look at what it means to “come” to a place.

“As what do I arrive? As a trader, a coloniser, just passing by, do I bring ideas, knowledge, my language, my habits, my religion, my arts? It depends.

“Because of the huge amount of Mycenaean pottery in Cyprus, people began to think already in the late 19th century that Myceneans had come and settled here – it was an indication of their actual presence,” he said.

Papasavvas added that Cyprus by this time had been receiving a considerable amount of goods and materials from the surrounding regions. These items did not travel by themselves – they were brought by people.

“One place may not receive just objects from another place, it may also receive and exchange ideas: these may be religious, political, or technological knowledge.

“So, amongst these imported materials there are many Mycenaean items – and some Minoan ones – especially from the fourteenth century onwards,” he said.

Here’s the kicker, Papasavvas emphasised: “There’s so much Mycenaean material in Cyprus of a very good quality – pots for example – that we find in Cypriot rich tombs, in some cases in larger amounts in Cyprus than in mainland Greece, where they came from.”

Schaeffer and others dated the arrival of Myceneans to the 14th century BC, but then other archaeologists – especially by the 1940s – claimed that the huge amounts of pottery are not an indication of colonisation or settlement, but of international trade, and that it was only later in the 12th century that Mycenaeans came to settle and brought their language with them.

“This is very important because in the 12th century we have a lot of upheaval and unrest in the Eastern Mediterranean; for example Mycenae and other Mycenaean citadels were destroyed and their inhabitants appear to have come in masses to Cyprus,” he said.

The archaeologist said that at some point from the 11th century BC – at the latest – Cypriots began speaking Greek.

But how did Schaeffer end up in a feud with Dikaios?

Schaeffer conducted research at Ugarit, in modern day Syria, from 1929 to 1969. The ancient coastal city lies just opposite the coast from where Enkomi is situated. Schaeffer found there many items linked to ancient Cyprus, which attracted him to the island, in the search of those Mycenaeans, who, he believed, had first sailed from the Aegean to Cyprus and from here to the opposite coast.

In other words, he believed that Ugarit had been a colony set out from Cyprus. Therefore, as Papasavvas puts it, Schaeffer’s interpretation of Enkomi was tied up with his interpretation of Ugarit, which had made him famous in previous years.

“If his interpretation of Enkomi was incorrect then that would have impacted his Ugarit work,” Papasavvas argues.

Dikaios began his work at the ancient site as it was so extensive that Schaeffer had requested assistance from the then British led Department of Antiquities of Cyprus.

They sent Dikaios. The two began digging side by side – in trenches, hence Papasavvas’ “trench warfare”.

“But Dikaios came to produce a completely different chronology and interpretation of Enkomi, which was opposing Schaeffer’s interpretation – so Schaffer was infuriated and tried to stop Dikaios,” Papasavvas explains.

Schaeffer essentially claimed the Mycenaeans had settled in the 14th century BC, while Dikaios said the 12th century BC, but the clash went much deeper.

“And you know, some archaeologists are very lucky – Dikaios was not only an excellent archaeologist, but he was also a lucky archaeologist, too. In the first days of his excavation he found this bronze statue of the Horned God – one of the most impressive finds ever in the Eastern Mediterranean. Schaeffer was envious – to say the least,” Papasavvas says.

Schaeffer eventually got his own ‘great find’ and uncovered another bronze statue at Enkomi, the Ingot God. The two statues discovered by the two rival archaeologists, described as being of equal importance by Papasavvas, are facing in each other in a standoff on the cover of the book.

“It was a very tense situation between them.”

“I stand with Dikaios, not only in the sense that he was correct in his interpretation, but also because he was a formidable archaeologist and a fair man – whereas Schaeffer used every means to prevent Dikaios from further digging at Enkomi and to keep the site for himself, claiming his absolute scientific authority over it. But in the end, it is Dikaios’ ideas and interpretation that have prevailed in archaeological thought, not Schaeffer’s,” he says.

Schaeffer’s strategy to keep Enkomi for himself included accusations levied against Dikaios that the Cypriot excavator was blinded by bias – he was a philhellene, the Frenchman said, a serious accusation at the time in British-ruled Cyprus.

“The first reason I wanted to write this book is to pay homage to Dikaios who did an incredible excavation and published everything, in a way that although it started some 70 years ago it feels very modern,” says Papasavvas.

“Dikaios was one of the pioneers in introducing modern methods of excavation and interpretation of archaeological finds, insisting on the importance all finds, even of the smallest sherds from broken vases, in order to reconstruct the lives of ancient people,” he says.

“Even now all this time later we can go through all the meticulous details in the publication of Dikaios so that we are able to reconstruct the process of excavation and interpretation and judge ourselves.

“That’s of crucial importance – particularly now that we don’t have access to the site, since it is situated in the occupied part of the island.”

The book is published by Astrom Editions, in the series ‘Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology and Literature’, which have produced a large number of authoritative books on Cypriot Archaeology.

The book is published by Astrom Editions, in the series ‘Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology and Literature’, which have produced a large number of authoritative books on Cypriot Archaeology.