The ‘safe’ narrative that our gas will go to Egypt for liquefaction is being turned on its head by events

As energy giants and experts gather in Nicosia on Monday, it’s growing increasingly clearer that a tectonic shift appears to be underway when it comes to the island’s energy policies fuelled by a renewed sense of urgency.

Two weeks ago, the announcement by Israeli leader Benjamin Netanyahu of a planned gas pipeline from Israel to Cyprus seemed like it dropped out of the blue, the disclosure apparently catching Cypriot officials off guard. But a closer look at the timeline shows the idea was around for a while. Beyond that, it signals a major reorientation of Nicosia’s energy geopolitics.

On May 16, Energy Minister George Papanastasiou ‘came clean’ after Netanyahu’s pipeline reveal two days earlier. He gave some details about the project, and then informed the public he’d return to Israel for talks aimed at clinching a state-to-state agreement. For many, it came as a bombshell. More on that later.

Papanastasiou explained the basic idea: a subsea pipeline from Israel to Cyprus would be used initially to bring natural gas here for power generation. The cheap fuel would help drive down electricity prices. However, that alone would not make the project cost-effective – the quantities needed by Cyprus are relatively small. To make it worthwhile, the project would also feature a facility on the island turning the gas into its liquid form, so that it would then be put on tankers and exported to Europe and elsewhere. In short, Cyprus would become a transit – or ‘hub’ – for Israeli gas. Killing two birds with one stone, so to speak.

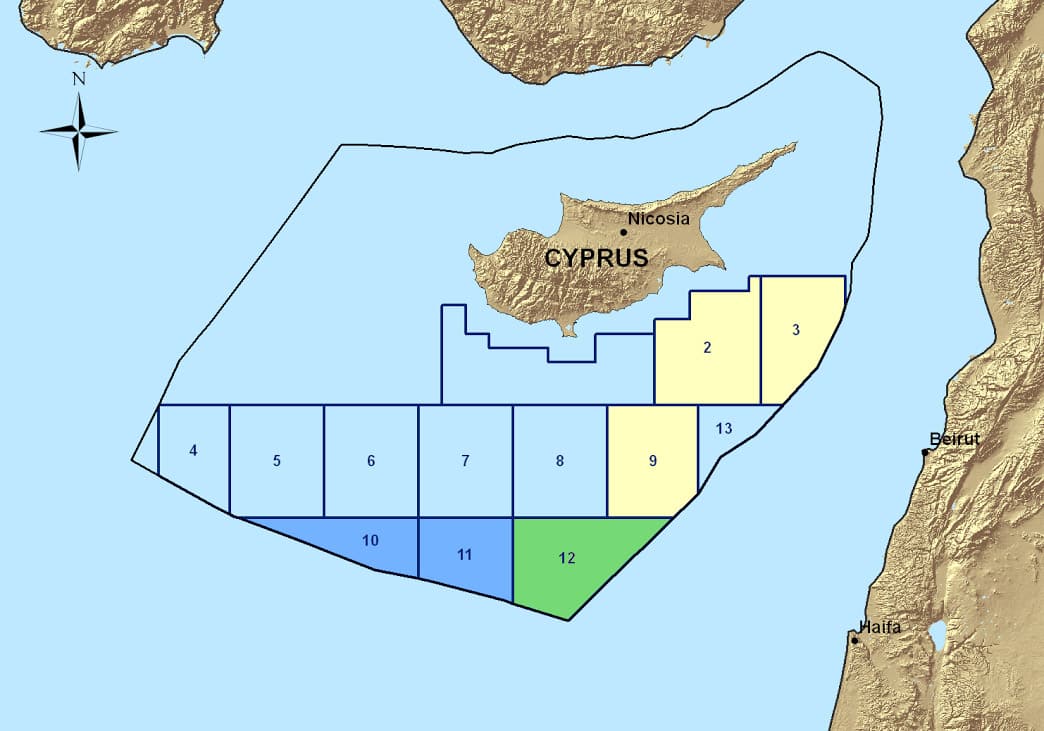

But the disclosure raised a host of questions. Here are some: why would we bring Israeli gas for liquefaction, when we have our gas reserves offshore? And does this amount to an admission that there are no plans to extract gas from Cyprus’ Exclusive Economic Zone? What about the Chinese-led project to import LNG for our energy needs – would the €300 million cost be written off by the time we import gas from Israel? Was this just another wasteful endeavour?

Moreover: why would Israel want to send gas to Cyprus when it already uses plants in Egypt for its exports? Also, in June 2022 the European Commission signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Egypt and Israel to export Israeli gas to the EU to end heavy dependency on Russian energy. The MoU got a lot of fanfare, with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen calling it a “historic agreement.”

And last, but not necessarily least, whose idea was this Israel-to-Cyprus pipeline? Tel Aviv’s or Nicosia’s? Or both?

We put these questions to Papanastasiou. A lot of moving parts, many dots to connect. Taken at face value, what came out of our conversation is a tectonic policy shift on the part of Cyprus.

“For many years there’s been the narrative about Egypt being the destination for our gas. It was the ‘obvious’ solution, yes, but not necessarily the best solution,” the minister said.

“It was a ‘safe’ narrative – our gas will go to Egypt for liquefaction. But no one really analysed this – what does it really mean?

“Energy companies in our EEZ say they want to take the gas to Egypt. OK but they have yet to explain how exactly – what infrastructures they’ll use.”

Though the minister was being tactful, it was not difficult to discern a certain frustration – even impatience – from the government.

Papanastasiou bottom-lined it for us:

“There are several reasons behind our pipeline proposal. First, we give priority to the inland market. Cyprus comes first. Second, you don’t want to put all your eggs in one basket. It’s good to have an alternative option beyond Egypt. That doesn’t mean the Egypt option is being discarded, and Egypt definitely remains a useful partner. And third, with this proposal you attract Israel – a major geopolitical player.”

But even if the Israel tie-in is ‘just an option’ – as the minister portrays it – it still telegraphs a massive realignment in thinking. In short, big doings underway.

On Monday (May 29) the minister will be speaking at a workshop in Nicosia, to be attended by energy execs from across the hydrocarbons chain. Reps of energy companies engaged in Cyprus’ EEZ will be there. Papanastasiou will analyse the Israeli pipeline proposal, and get feedback.

One can almost sense he’s twisting the arm of the energy companies. Later, in mid-June, Papanastasiou will fly to Israel for talks geared at concluding the pipeline deal. It’s all moving fast.

And it looks like the Cypriots mean business – as do the Israelis. The Sunday Mail learns that the delegation accompanying Papanastasiou will include legal and energy experts. They’ll spend two days in Israel.

Incidentally, on Friday (May 26) Papanastasiou and President Nikos Christodoulides met with a delegation of Chevron, the operators of offshore Block 12 where the untapped Aphrodite well is located.

Coming out of the meeting, Papanastasiou said the oil major was “positively disposed” toward supplying natural gas to Cyprus from Aphrodite.

The company presented a “preliminary plan” to develop Aphrodite, which the government would look over.

‘We pointed out to them the need to supply the Republic of Cyprus with natural gas for power generation, something which the company did not reject, telling us it was one of the plans it could explore.”

So how does it all come together? The mooted subsea conduit from Israel will follow the same route as that indicated in the plans for the EastMed pipeline. The gas arrives in Cyprus, some of it gets diverted for domestic electricity generation, the rest liquefied separately and exported via tankers – this second part is what Papanastasiou dubbed the ‘EastMed corridor’.

As it happens, the pipeline from Israel would pass just 60km west of the Aphrodite well – meaning a connection to the reservoir is quite feasible. That’s how you draw in the Aphrodite concession holders.

“The conduit will end up at Vassilikos, whereas the liquefaction facility would likewise be located in that vicinity,” Papanastasiou tells us.

Also, a T-junction will be built somewhere along the last stretch of the pipeline, creating a ‘fork’ to Dhekelia and the power plant there. The natural gas must link up to Dhekelia as well, for technical reasons – to balance the grid.

As for the facility liquefying the Israeli gas at a subsequent stage, it will be located either on land, or as an FLNG (Floating Liquefied Natural Gas) facility – again in the vicinity of Vassilikos.

“The gas from Israel would come from one or more Israeli fields. Take your pick,” remarks Papanastasiou, refusing to be drawn further.

From his comments, one can infer that a great deal of thinking has gone into the project – boosting the perception that the upcoming trip to Israel will involve putting the finishing touches.

So the general outline of the idea is taking shape. Here, we put the aforementioned queries to the minister, starting with: why would we import gas from Israel when there are reserves lying just off Cyprus:?

“A valid question,” he offers, and leaves it there.

Next: why would the Israelis send us their gas, when they’re already trading with Egypt, not to mention signing that MoU with the European Commission?

“An MoU is a statement of intent, not a binding agreement,” the minister replies. “As for the Israelis already exporting their gas to Egypt, that’s no problem – they’ve got enough to send both to Egypt and to us.”

We also challenged the minister about the investment in the Chinese LNG project at Vassilikos, plagued by delays. Would the €300 million be written off by the time the Israeli gas gets fed into Cyprus’ grid?

“Speaking of €300 million, we pay about that amount a year in greenhouse gas emissions allowances,” he counters.

The Sunday Mail next put it to Papanastasiou how recently he spoke of how Cyprus needed to change its focus from large-scale projects to small-scale projects. But isn’t he contradicting himself now, since the pipeline from Israel is arguably such a large-scale endeavour?

“Not really,” he says. “We’re talking about a 190km pipeline, so not that large. Compare and contrast to the EastMed pipeline which would run for 1,900km.”

So did the reveal about the Israeli pipeline/liquefaction plant come like a bolt out of the blue? To most it did. It shouldn’t have.

In early March – more than two months ago – Netanyahu paid a working visit to Italy. There, he spoke of a “quantum leap” in relations between the two nations. The visit got a lot of play in Italian media.

It was Netanyahu’s first trip to Italy’s capital since Giorgia Meloni took office, coinciding with Rome’s search for alternatives to Russian gas.

At a business forum in Rome, the Israeli leader laid it out. He told Italian Enterprise Minister Adolfo Urso:

“We have gas reserves that we are now exporting and we’d like to expedite more gas exports to Europe through Italy. I think this (gas) is a strategic need of Italy and Europe, and Israel is prepared to do more with you for that end.

“We are already cooperating in gas with your national company (energy giant ENI) but we want to expand it. I think we should look very carefully and quickly at the possibility of adding an LNG facility, perhaps in Cyprus, to increase Israel’s export capacities of gas to Italy, and from Italy to Europe.”

And there it was – that reference to Cyprus.

“But it seems nobody in Cyprus was listening, they didn’t realise he was trying to tell us something,” says another source, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Fast forward to Sunday, May 14, when Netanyahu breaks the ‘news’ about the pipeline to Cyprus. He then says the issue was discussed between the two governments during President Christodoulides’ visit there.

Christodoulides got back from Israel on May 12. Not a peep about the pipeline. Then two days later Netanyahu dropped the ‘bombshell’, and the Cypriot government had to start talking.

It’s clear the two sides were in advanced talks about the issue, keeping it quiet, but for some reason Netanyahu decided to spill the beans.

Whose idea was it? It’s possible it was conceived by Tel Aviv, with Nicosia picking up on it and deciding to ‘tack’ Cyprus onto Israel’s ambitious gambit to supply an energy-starved Europe. Or they were both in on it from day one.