Turks voted on Sunday in one of the most consequential elections in the country’s 100-year history, a contest that could end President Tayyip Erdogan’s imperious 20-year rule and reverberate well beyond Turkey’s borders.

The presidential vote will decide not only who leads Turkey, a NATO-member country of 85 million, but also how it is governed, where its economy is headed amid a deep cost of living crisis, and the shape of its foreign policy.

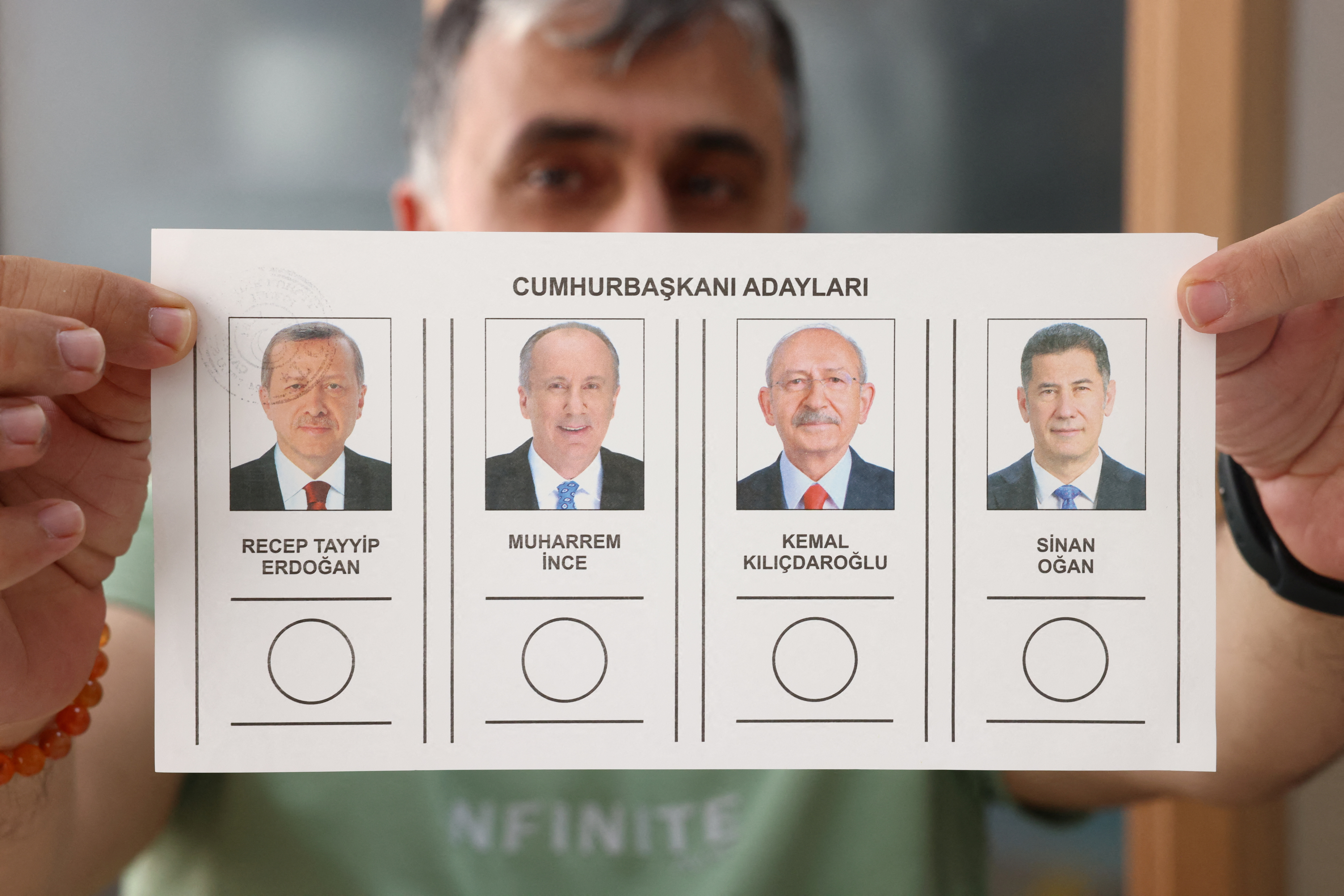

Opinion polls have given Erdogan’s main challenger, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, who heads a six-party alliance, a slight lead, with two polls on Friday showing him above the 50% threshold needed to win outright. If neither wins more than 50% of the vote on Sunday, a runoff will be held on May 28.

Polling stations in the election, which is also for a new parliament, closed at 5 p.m. (1400 GMT). Turkish law bans the reporting of any results until 9 p.m. By late on Sunday there could be a good indication of whether there will be a runoff.

With Erdogan slightly trailing his rival, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the elections are being intently watched in Western capitals, the Middle East, NATO and Moscow.

A defeat for Erdogan, one of President Vladimir Putin’s most important allies, will likely unnerve the Kremlin but comfort the Biden administration, as well as many European and Middle Eastern leaders who had troubled relations with Erdogan.

Turkey’s longest-serving leader has turned the NATO member and Europe’s second largest country into a global player from Libya and Syria to Ukraine, modernized it through megaprojects such as new bridges, hospitals and airports, and built a military industry sought by foreign states.

But his volatile economic policy of low interest rates, which set off a spiralling cost of living crisis and inflation, left him prey to voters’ anger. His government’s slow response to a devastating earthquake in southeast Turkey that killed 50,000 people added to voters’ dismay.

ilicdaroglu has pledged to set Turkey on a new course by reviving democracy after years of state repression, returning to orthodox economic policies, empowering institutions who lost autonomy under Erdogan’s tight grasp and rebuilding frail ties with the West.

Thousands of political prisoners and activists, including high level names such as Kurdish leader Selahattin Demirtas and philantropist Osman Kavala, could be released if the opposition prevails.

POLARISED

“I see these elections as a choice between democracy and dictatorship,” said Ahmet Kalkan, 64, as he voted in Istanbul for Kilicdaroglu, echoing critics who fear Erdogan will govern ever more autocratically if he wins.

“I chose democracy and I hope that my country chooses democracy,” said Kalkan, a retired health sector worker.

Erdogan, 69 and a veteran of a dozen election victories, says he respects democracy and denies being a dictator.

Illustrating how the president still commands support, Mehmet Akif Kahraman, also voting in Istanbul, said Erdogan still represented the future even after two decades in power.