THEO PANAYIDES meets a dramatic woman, not held back by convention, who follows a globe-trotting life bringing the benefits of pre-Hispanic traditions to the world

The name is majestic in itself: Patricia Elizabeth Torres Villanueva. Back in school, she explains, at the German school (she was born in Guadalajara, in the state of Jalisco), she was always ‘Patricia Torres’, but “for my family, I am Elizabeth”. Older friends tend to use her second name, more recent friends the first one. The story behind it is revealing – because her actual name, the one her mother wanted, is ‘Elizabeth’, “but in Mexico at that time, when I was born – a long time ago, many springs ago! – the Church obliged you to put the name of the saint on the day you were born”. She was actually quite lucky: she was born on March 17, St Patrick’s Day – hence ‘Patricia’. A day later and she might’ve been landed with Blessed Celestine of the Mother of God, or St Frigidian of Lucca.

But there’s something else too. “That is my religious name,” she says, of ‘Patricia Elizabeth’. “My indigenous name, that the indigenous people gave to me in accordance with the calendar, is Tezcacoatzin. So the indigenous communities, they know me by Coatzin.” That name may suit her best of all, if only because of its meaning: ‘Precious energy of life’.

It took years to be accepted by the indigenous communities – some two million souls scattered around the mountains of Mexico in places like Guerrero and the Sierra Norte del Puebla, preserving their “oral tradition, their rituals and ceremonies”. Patricia Elizabeth was already in her 40s when she first approached them, having spent two decades living in Germany, working first as a trade official (“attending all the main fairs in Europe, and increasing the business relationships between Mexico and Germany”) then as a Freudian psychoanalyst before seguing into anthropology and eventually dance. “My specialty,” she explains, “is dance therapy,” indeed she lectured on ‘Therapeutic aspects of pre-Hispanic dance’ as far back as 2005, at the World Congress on Dance Research that took place in Larnaca. She’s been coming to Cyprus for a while, though it’s just one stop in a globe-trotting life: after this she’s off to Athens, then Prague, back to Mexico for a few days, then Colombia, Buenos Aires, and Minnesota for a ‘powwow’ of First Nations peoples.

We meet in a flat in Engomi, her local base for a few days while teaching workshops at Dance House Lefkosia and the Tree of Life Centre in Larnaca. She opens the door, surveilling me with lively grey-green eyes. Her personal style is dramatic – a dancer’s style – with gracious motions and occasional squeals of delight and mock-horror; everything is ‘darling’ and ‘my darling’. She seems both regal and up for anything; she’s unflappable, probably unshockable. Patricia Elizabeth is alone in the flat apart from Lupita, a younger woman who I assumed was a personal assistant but is actually a specialist in traditional medicine with a focus on the temazcal, a Mexican variation on the sauna with a more therapeutic bent. Two Mexican cultural centres are being planned to open soon – with temazcals attached – in Limassol and Larnaca.

It’s Lupita who fetches the conch, for demonstration purposes, along with jangling chains of ayoyote husks. “I don’t know if the neighbours might be scared…” murmurs Patricia Elizabeth as she cradles the large shell – but goes ahead anyway, starting off with the conch held to her breast. Next to my heart, she explains, the here and now – “I am aware. You see? How can I be depressed when my heart is beating, my whole systems are working?” – then extends it outwards with both hands, then up to the sky, then down to the ground: “From my heart to the heart of the earth, to the heart of the cosmos, I give thanks for the energy that gives movement to my body. From the earth to the sky, and from the sky to the earth. And then I inhale…” She does so – then exhales, blowing into the conch and emitting a loud, reverberating hum that soars into the quiet Nicosia neighbourhood and would surely be followed, if this were a movie, by the howling of faraway dogs.

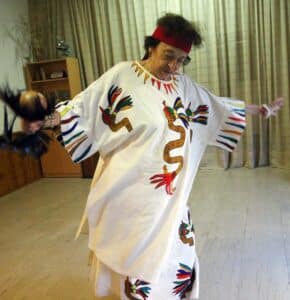

The conch is part of the rituals, the old pre-Hispanic traditions. “I will show you my dress that has my name,” says Patricia Elizabeth. “Because we have symbols. We didn’t have written language, so we have only symbols.” Lupita brings matching white dresses with elaborate snake-like symbols – actually the same symbol four times, signifying the four stages of life (“Child, young, mature, old”) and the fact that all four are present in a person at the same time. Four seems to be a significant number. There are four basic steps in most of the dances she teaches, and four important things in life – which, in order of importance, are breathing, water, sleep and nutrition. What does she do to maintain her own energy? Again, the answer has four parts: “I eat healthy, I breathe healthy, I sleep healthy, and I am in contact with Nature”.

She’s two people, professionally speaking, both quite prominent in their respective fields – and they come together in dance therapy, her assertion that the rhythms of pre-Hispanic dance (reinforced by the stomping of feet that accompanies the dance) “are like medicine”, and can actually alter our mind chemistry. On the one hand she’s an anthropologist and researcher who’s taught at universities and presented her work at conferences; on the other she’s a psychoanalyst, with clients all over the world. One of the more surprising aspects to Patricia Elizabeth is that she has four children, all adopted, from various places: Germany, Toronto, Poland and Austria. “I am a psychoanalyst,” she reminds me. “I was like their godmother, and when they were teenagers they said ‘Save me, I don’t want to live with my parents anymore!’.”

She laughs, but the rather unconventional arrangement was quite serious: she legally adopted the kids – their parents agreed – and brought them to live with her, as a kind of extended therapy. They weren’t abused, just unhappy; one boy, for instance, had asthma because he felt like his parents (who’d married too young) were “choking” him, unconsciously blaming him for the way their lives had turned out. Once in Mexico, in Patricia Elizabeth’s house by the sea – she’s in Manzanillo, on the Pacific coast – his asthma vanished, “and then he went back, and he’s now a very happy person”.

It’s a bit unusual, not exactly standard practice for a therapist, but that doesn’t seem to faze her; she seems – as already mentioned – to be up for anything, unconstrained by convention or official policy. Her late husband was 20 years younger (that’s unusual too) but in fact they matched nicely, dancing and giving lectures together. She began as a student radical in the ferment of 1968, so much so that her father had to intervene, relocating her to Germany for her own safety – and her faith in dance as medicine is also quite radical, though her two sides approach it in different ways. The psychoanalyst views it in terms of wellness. The anthropologist views it in terms of history.

The wellness angle is perhaps controversial, in this age of institutionalised medicine – can dancing really ‘enhance’ the rhythm between our two brain hemispheres? – but the history angle is just as controversial. “If you don’t believe anything that I say, go and look. Find out!” she implores, acutely conscious of the fact that official history – as ever – was written by the winners, the conquistadors. “I wanted to know the real truth of the codices, the ancient paintings.” (Codices are hand-painted pre-Hispanic books, almost all destroyed or repainted by the Spanish invaders.) “Because the chronicles of the 16th century, written by the Spaniards, don’t say the truth. They say what they think it was – but they never learned the language, they never understood us. They even said that we were animals, that we didn’t have any soul. Because they couldn’t cope with the nobility of the people.”

The history of Mexico, in Patricia Elizabeth’s telling, is a story of greed versus civilisation, made worse by cultural misunderstandings. “This is the salute of the Mexican people,” she explains, raising both hands in the air; that’s what Montezuma did when Cortes tried to shake hands – and Cortes, uncomprehending, was offended, feeling he’d been rebuffed. At the entrance to pre-Hispanic cities were symbols of the various professions: a disc of gold signified scholars, jade meant farmers. “This is what I want,” declared Cortes, grabbing the gold – but the people assumed he meant knowledge, not gold itself; “So we never understood what they were talking about”. Her view of the pre-Columbian past is idyllic; talk of human sacrifice is just propaganda, indeed she recalls a Swiss ethnographer visiting Mexico while she was still at university offering proof that it wasn’t true, that it’s physically impossible to carve someone’s chest open with the type of knife the Aztecs are supposed to have used. (The authorities gave him 24 hours to leave the country.) “We’d mastered chemistry, physics, astronomy, mathematics – we were very advanced,” she sighs. “But they were only interested in gold and silver.”

Some may find it simplistic, this vision of an Eden destroyed – but it fits with her sense of drama, a certain instinctive flair for the grand statement in those who are gifted and unconventional. Patricia Elizabeth is indeed quite majestic. She’s fluent in eight languages (she was already trilingual at the age of five, thanks to the German school) and, though the family weren’t poor – her dad was a businessman – won one scholarship after another in pursuit of education. I suspect she’s always chafed against authority, the patriarchal Mexico of her youth, the Church that imposed even her own first name. At one point we talk about couples, and I mention the ‘opposites attract’ theory of men and women completing each other – but she shakes her head: “Not ‘complete’. Nobody can complete me, that’s a fantasy. I am complete the way I am! I need somebody here who’s like me. That’s what ‘couple’ means, two of the same kind.”

But don’t extroverts need introverts, and vice versa?

“Nooo!” she squeals in horror. “My God, if an introvert marries an extrovert this is horrible, the most horrible thing that you can ever do. No, my darling, nooo! Two extroverts are happy, because they are extroverts.”

It makes sense, in a way. She’s regal, as already mentioned, the grande dame – the queen – of pre-Hispanic dance; a queen needs a king, not some shy little man. Meanwhile she lives her life, travelling half the year to see clients and students (she presided over daily dance classes on Zoom during lockdown, “43 countries dancing together”), working fastidiously on her own wellness. Breathing, water, sleep, nutrition, in that order. Nutrition means eating seasonally, “you have to eat what Nature gives you”. (Right now, in Mexico, it’s a potato-like root called chinchayote.) Water means no alcohol – and in fact she’s never drunk, smoked or taken drugs in her life. Has she never been tempted to expand her mind a bit? “No! No, no! I can do that with dance… There is nothing more delicious than a glass of water. Nothing.”

Alas, the rest of the world isn’t so fastidious. Mexico is also known for substances like peyote and ayahuasca, and she roundly disapproves of the way such psychedelics are slowly becoming legalised in the US and Europe. Kids suffer from a different addiction – “We call this the smoked mirror,” she proclaims, holding up her smartphone, meaning a fake reflection of reality – and “we’re very worried what’s going to happen in 20 years to all these kids”. Then there’s her own predicament, the simple fact that she’s now in her fourth stage of life. Is she afraid of dying?

“Me?” she squeals again. “Death doesn’t exist, darling.”

I start to protest – but of course she means it culturally, not literally. The skull is a symbol of life, not death, in Mexican culture, just another of the many transformations we go through. Patricia Elizabeth has gone through her own transformations – there are three identities in her name alone, when you include ‘Coatzin’ – but the common thread is what she calls presence, being aware, like the body’s awareness of rhythm in the throes of dance. (She quotes the poet Facundo Cabral: “You are not depressed, you are distracted… You are not paying attention.”) “You know, when I inhale I am alive,” she muses. “I am with myself. When I exhale” – she does so – “I don’t know if I’ll be inhaling again”. She shrugs mildly: “When it’s my last breath, it doesn’t matter. Because I lived in the eternal present. So I enjoyed every minute of my life.” Precious energy of life, indeed.