In a former tabloid journalist THEO PANAYIDES finds an impulsive woman, mentally tough and an animal lover who his now tired of peeking into other people’s lives

We’re about an hour in, sitting at Meraki – an impressive vegan caff on the beach road in Chlorakas – and Andrea Busfield is waxing briefly philosophical on life in general. “It’s like being in your own drama, life, isn’t it?” She sighs, and says something I’ve never heard a profile subject (or any other human being) say before: “I dunno, I think probably what messed with my head was seeing the play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead too young”.

That’s Tom Stoppard’s existential comedy, for the uninitiated, in which the two minor characters from Hamlet live their own, largely inconsequential lives on the fringes of Shakespeare’s classic, their absurdist exploits sometimes converging with the prince of Denmark’s. Everyone’s life is their own little universe, is the lesson here, “and then suddenly you’re called in to someone else’s universe”. That’s what happened during Andrea’s years as a tabloid journalist (The Sun from 1996-2000, then the News of the World from 2000-05), when she made her living by peeking into other people’s lives – but that’s also what happened in Afghanistan, which she covered as a war reporter then as chief civilian print editor for a Nato rag called Sada-e Azadi (‘Voice of Freedom’), and it’s even what happened earlier, in her teens, when she devoted her life to “following bands instead of studying, cause that seemed far more interesting”. Only now, in the past 11 years in Cyprus, has her universe become more self-contained, less prone to outside interference – and it’s all because of animals.

They know her well – I presume – at Meraki, and don’t take it badly when she only orders an orange juice. (I have a complicated smoothie with dates, bananas, coffee, oat milk and chia seeds.) They can probably tell she’s in a dark mood, having just received “some upsetting news regarding the care of my animals” – but the mood lightens as she starts to talk about her life, starting once again in Cyprus, and being evacuated in 1974 at the age of four (her dad was in the RAF), then moving on to her couple of years as a so-called ‘follower’ when she really should’ve been studying for A-Levels. “I think I came away with one A-Level,” she recalls cheerfully. “In Politics – just from watching the telly.”

They know her well – I presume – at Meraki, and don’t take it badly when she only orders an orange juice. (I have a complicated smoothie with dates, bananas, coffee, oat milk and chia seeds.) They can probably tell she’s in a dark mood, having just received “some upsetting news regarding the care of my animals” – but the mood lightens as she starts to talk about her life, starting once again in Cyprus, and being evacuated in 1974 at the age of four (her dad was in the RAF), then moving on to her couple of years as a so-called ‘follower’ when she really should’ve been studying for A-Levels. “I think I came away with one A-Level,” she recalls cheerfully. “In Politics – just from watching the telly.”

She wasn’t a groupie in the old 1960s sense, “we didn’t sleep with the band or anything… But we used to follow them from venue to venue, and just hitchhike all around the country”. Andrea and her best friend Janie would set off for wherever ‘their’ bands were playing, and meet up with the 20-30 other hardcore young girls who’d arrived from other parts of the country. The bands weren’t exactly Top 40 material: “I think at the time ‘grebo rock’ was the sensation – so you had bands like Crazyhead, the Bomb Party and Gaye Bykers on Acid”. The girls weren’t friends with the bands, they didn’t hang out (in any case, she says, “I was around 17, I was a bit shy”), but the followers were well-known to the crew and usually on the guest list for the concert, their only job being to stand at the front, dancing madly – then on to the next gig. It was a strange arrangement.

Were her parents relaxed about all this?

No, she laughs, they were “absolutely not relaxed! But what can they do, when you’ve got a 16-17-year-old who will just do things?”.

That may indeed be a fair description of Andrea Busfield, a woman who’ll often ‘just do things’. “I don’t overthink,” she admits. “I don’t have some Macchiavellian plan to do anything… I just have a gut instinct about what I need to be doing.” She always knew she wanted to be a journalist – “I had my first byline when I was 10, in [RAF magazine] Tornado Talk” – and was instantly good at it, having skipped uni (especially with only one A-Level) for a one-year pre-entry course followed by immersion in the work itself. “Journalism’s one of those amazing professions,” she muses, “where, if you can do the job, it doesn’t really matter what qualifications you’ve got. All you need is a foot in the door.”

She was bad at finding stories, she admits, being “intrinsically lazy” – her bio on Twitter (now X) reads: “Writer, plant eater, dog collector, horse lover and professional lazy girl” – but excellent at “reading people” and also known as a safe pair of hands, meaning she wouldn’t inflate or sensationalise. One of her biggest triumphs was actually a story she didn’t do, when the News of the World sent her to Brazil to interview a model that racing driver David Coulthard was supposedly having an affair with; the paper had already spent a lot of money on the story – but Andrea smelled a rat, especially when she saw the young woman’s passport was almost blank (it should’ve been full of stamps, had she been swanning around Europe with Coulthard), and advised them not to run it.

The story didn’t run, but the memory lingers: taking a private plane to meet the model somewhere in the Amazon, then interviewing her in a hotel room accompanied by “two rather feral cousins” who spent their time raiding the minibar. Memories abound from the journalistic life, painful and beautiful and often both together. Working at The Sun on Christmas Day, for instance, still in her 20s, and covering the story of a taxi driver who’d been stabbed to death for 50 pence (he’d just been starting his shift): “I was sent round to the house – basically to do a ‘death knock’. On Christmas Day. Yeah, harsh”. It turned out that the dead man had been pretty amazing, a lovely soul who’d fostered many kids together with his wife – “He was my guiding light,” she told Andrea; “He was my everything” – so much so that Andrea sacrificed the exclusive and opened her notebook to any journalist who wanted the story. And of course there was Afghanistan – a place where she might equally find herself on a magical mountain peak amid a carpet of clouds or looking at “three bodies with limbs torn away, obviously from a landmine or something, and someone had defecated on the chest because they were foreign fighters.”

Was she okay seeing horrors like that?

“Yeah,” she replies thoughtfully. “I’m not so good with illness, or injury – but death was really quite easy. It’s like I see it, but they don’t look real. None of it looks real, they look like dummies… So no, I never had a nightmare about it.”

Actually, she’s never had a nightmare at all – just as she’s never felt lonely in her life, two unrelated feats that nonetheless may derive from a common source, a mental toughness. Her dream life is under control: “If a dream is going a way I don’t like, say it’s a bit creepy or something, I wake up. Then I go back to sleep, and it doesn’t come back”. Her emotional life is also under control. “I don’t need community. I’m quite self-sufficient,” she replies without rancour when I ask if she’s part of the British expat community in Paphos. (She does have friends, but is largely “on the fringes”.) Her longest relationship was with an Austrian soldier she met in Afghanistan – and she even moved to Austria for three years, but it didn’t take. “It wasn’t like there was a lack of love, there was love… He was a good man – but I wasn’t happy. And I’ve not found anybody who’s been better than him, so why would I settle? I know some women struggle on their own – but I’m not one of them.”

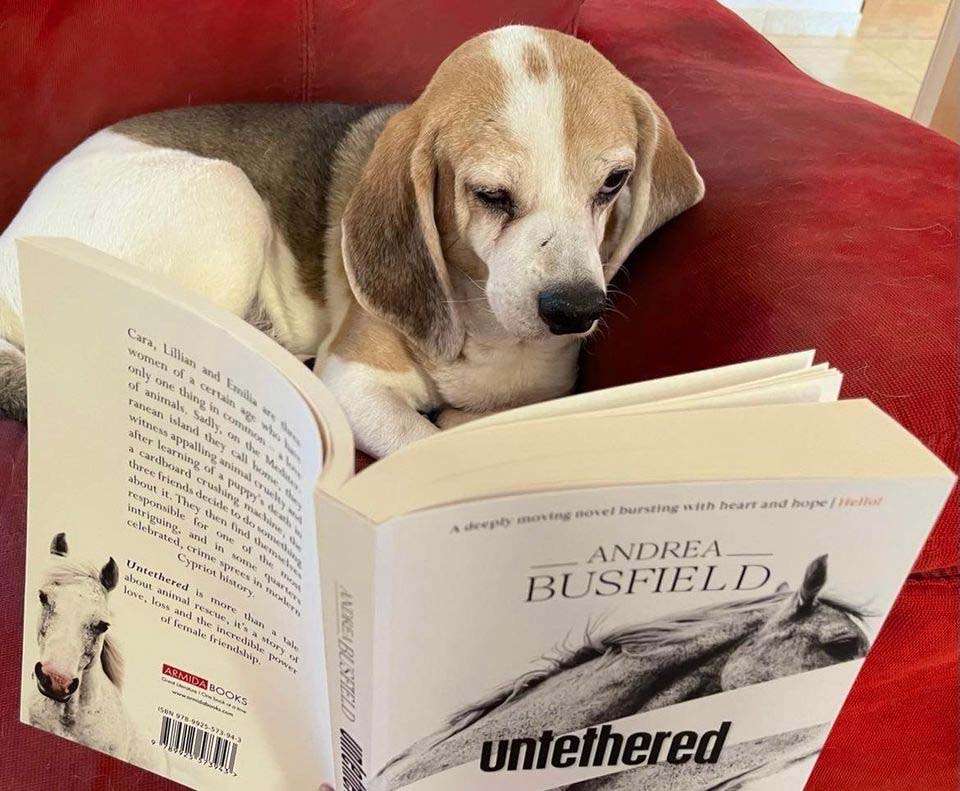

There’s one important factor underlying that rather bold statement, and that’s animals. “If I’d had horses in Austria, I probably would’ve stayed,” admits Andrea. “Because it’s the horses that have made me content in life.” It started with Blister, a street dog she rescued in Kabul, and soared to a whole new level in Peyia with Achilles, her first-ever equine companion; the household now includes three cats, five dogs and – last but not least – three horses, Lucky, Mina and Sundance. “It’s like dogs are my companions,” she says, trying to articulate the difference between the two animals, “[but] the horses are my passion”. Andrea published a novel last year (her third) called Untethered, about a trio of quirky vigilantes battling animal abuse in Cyprus, the implicit message of the book – I suggest – being that relationships with animals are ultimately more important than those with other humans. She nods in agreement.

Why is that, exactly?

“It’s an unconditional love, like we all kind of want. Um…” She hesitates, trying to find the words: “They’re just easier to be around. And they’re easier for me to be me around, as well. And I do get a sense of stillness with them – which I don’t get from being around people”.

That craving for stillness is relatively new; back in the day, she was all about doing things (a hangover, she suspects, from her days as an RAF kid, forever moving on to the next place) – and, though she could always write well, she wasn’t exactly an intellectual. “I liked Big Brother and all that stuff, I wasn’t really watching the History Channel.” (She later did a year as the News of the World’s TV critic, an overdose so fatal she hasn’t even owned a TV since.) “I might’ve been left-leaning in my politics, just as a natural gut reaction to the way the world is. But I wasn’t political as such.”

Once again, the impression is of someone who fields what the world seems to throw at her, without overthinking too much – which was also what allowed her to be (or appear) fearless in Afghanistan, the way she’d plunge in with a ‘what will be will be’ attitude. That whole life-changing sojourn only happened by accident: she’d been on holiday in Cyprus during 9/11 and, by the time she got back to London, all the other reporters were already in America – and there was another “fantastic misunderstanding” later, when a Northern Alliance contact thought she was working for Newsweek rather than News of the World and set her up with a very important warlord, Haji Qadeer, who became her mentor in the country. Hearing the name for the first time, she scribbled it down in her notepad as ‘R.G. Cardear’. “I know, I know! I had very little knowledge, in fact I’d gone over with only the Lonely Planet guide to Central Asia” – a book that included the following snippet: “The best time to go to Afghanistan is don’t go”.

She did go, of course – and it changed her life, that unique mix of magic and cruelty, though she reckons she’s not so different now from when she was young. “I’m still impulsive,” says Andrea. “I still speak honestly, when I should keep my mouth shut. I can’t stand injustice in any of its forms, whether it’s with people or animals – especially animals, because they have no agency to look after themselves.” For all the activism, she doesn’t seem abrasive; she’s fun to chat with, especially when her mood lifts and she starts regaling me with war stories. It may be significant that she and Janie, her old teenage friend, are still best mates, just as it’s significant that she and her parents remain close, despite all the angst she put them through. There’s a certain sentimental streak – and, for instance, she still holds on to her old Ford Puma, a 24-year-old jalopy, though “she [the car] can’t even get to Limassol now. So I think I’m going to have to let her go. That’s going to be the hardest part of leaving Cyprus.”

Wait, she’s leaving? Yes indeed. Cyprus changed her life, much like Afghanistan, because of the horses (she spends most of the day with her animals, then works as a freelance copy writer in the evenings) – but now it’s time to leave, also because of the horses. Andrea is off to rural Ireland, looking for a place where the horses can graze in green fields – an acre per horse would be nice – and where, most importantly, she can live alongside them. Once again, she’s not overthinking it. “It just feels like the time is right”.

Sounds like it could be a solitary life; then again, she’s never lonely. She never married, and doesn’t think she ever will now. “It’s never been important to me. And now I can’t actually see myself sharing my life with anybody, I’m too set in my ways. Despite everything, I don’t really like drama – I don’t like the drama other people bring to my life. I would like to withdraw, and just live a very quiet existence with my animals.” The woman who once poked her nose into other people’s universes has lost interest in drama, even her own. She’s happy with the stillness and serenity of animals, the wordless connection, “a sense of belonging I get with the horses” – and a half-century’s worth of random memories, a life lived on impulse.